INSIGHTS

When Will U.S. Federal Budget Deficits Matter? January 2020

Executive Summary

In arguing for another round of tax cuts in 2002, Vice President Cheney famously remarked “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.” The Trump administration has embraced this approach, and the federal government now runs a deficit as large as that in the depths of the recession.

Politicians with populist tendencies from both parties are now drawing intellectual support for higher government deficits from proponents of what is referred to as “Modern Monetary Theory.” Oversimplified, MMT says that a government that borrows in its own currency isn’t constrained by deficits because the bonds it issues can always be repaid by printing the currency. MMT is a misnomer given that it is more about fiscal than monetary policy, and it is not so much a theory as a policy prescription.

This article outlines some of the problems with MMT, while noting that its precepts have largely been adopted over the last decade and that even greater deficits are very likely in the coming years. However, both monetary and fiscal policy are likely to remain stimulative for now. Eventually, the delicate balance among budget deficits, debt levels, interest rates, and inflation will become unstable, but that is not a story for 2020.

For decades, the expanding U.S. government debt and the federal budget deficit have been fixtures on investors’ lists of worries. With the Great Financial Crisis and its powerful deflationary forces, this concern took a backseat to the need for deficit spending to manage through that crisis. But now, with one of the strongest economies in many years, we are running a deficit as large as that in the depths of the recession.

Although it is hard to see much in the way of deficit concerns reflected in the current bond market, some investors are beginning to focus on when markets will again begin to care about federal budget deficits.

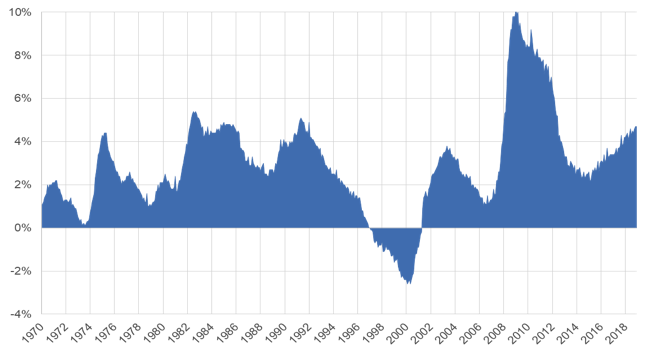

Some Budget Deficit History

For most of the 20th century, the U.S. ran fairly balanced budgets outside of bad recessions or war. The Republicans were the party of fiscal discipline, defending the nation’s debt status against the Democrats’ spending proclivities. With Reagan however, the GOP shifted strategy, opting for large tax cuts and subjugating concerns about deficits to a focus on growth stimulus from lower taxes. Clinton, benefitting from a strong economy and constrained by a GOP congress, ran surpluses for much of his term. Under Bush, in arguing for a second round of tax cuts Vice President Cheney famously remarked “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.”[1]

During the Great Financial Crisis, the federal deficit reached 10% of GDP in FY 2009, the peak year for the ARRA stimulus act and the bank bailout. This fiscal stimulus, coupled with the Federal Reserve’s aggressive monetary policy, enabled the U.S. to recapitalize its banking system and to steadily improve aggregate demand, economic growth, and employment. In the Euro-zone where constraints on fiscal stimulus measures were far more severe, the policy response involved much less fiscal stimulus but even more radical monetary policy measures, eventually including negative rates. The Eurozone’s policy responses were slower to revive their economies, but they clearly impacted U.S. capital markets, putting downward pressure on U.S. interest rates.

Figure 1: U.S. Treasury Federal Budget Deficit or Surplus as a % of Nominal GDP

- Source: usgovernmentspending.com

[1] Chicago Tribune, January 24, 2004.

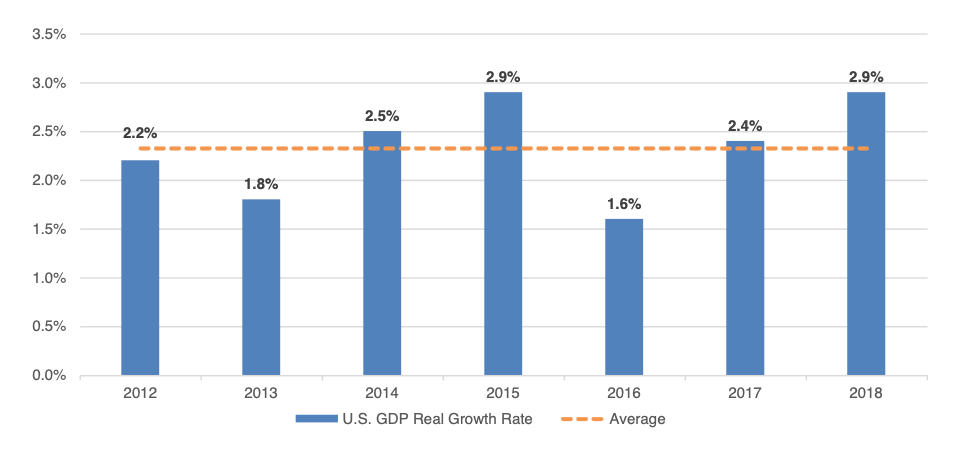

Trump’s Fiscal Stimulus

Trump campaigned on a platform of policies that he claimed would accelerate real U.S. GDP growth to the 3-4% range from the ~2% growth of the Obama years.[2] According to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, the tax cuts enacted at the end of 2017 increased the 2018 federal budget deficit by an amount estimated at 1.55% of GDP), and increased the 2019 deficit by an amount equal to about 1.73% of GDP[3]. GDP did rise in both years as shown in the table below, but by nowhere near enough to support GOP claims that the 2018 tax cuts “would pay for themselves.”

It is no surprise that the self-described “king of debt” has relied heavily on deficit spending to boost economic growth in a way that would pay near-term returns in his presidency, with any future reckoning deferred to down the road. This is what populists do. Trump rode a wave of populism into office that was not something he created and that is on the ascendency in both U.S. political parties as well as abroad. While the democratic presidential candidates favor higher taxes than does the GOP, many of them are promoting policies that would likely net out to deficits well above those that Trump is running.

Figure 2: U.S. GDP Real Growth Rates

[2] “Trump’s Formula for Growing the U.S. Economy, February 16 2018, www.brookings.edu

[3] Congressional Budget Office, “Budget and Economic Data – 10-year Projections.”

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)

Politicians with populist tendencies are now drawing intellectual support for higher government deficits from academics and other proponents of what is commonly referred to as Modern Monetary Theory or “MMT.” Oversimplified, MMT says that a government that borrows in its own currency isn’t constrained by deficits because the bonds it issues can always be repaid by printing the currency.

MMT is a misnomer given that it is more about fiscal than monetary policy, and it is not so much a theory as a policy prescription. MMT’s prescriptions for the low growth, deflationary world of today’s advanced economies go as follows:

- When monetary rates are near zero, central banks cannot effectively stimulate the economy, so fiscal policy must do the heavy lifting.

- Deficit spending and rising government debt are the only way to offset deficient private sector debt so as to prevent a fall in nominal GDP.

- Central banks should never tighten, but simply buy as much government debt as needed to keep interest rates low.

- In a country with its own currency, there is no constraint on spending as long as interest rates can be kept below the growth rate. If inflation rises, spending can be curtailed to bring interest rates lower.

As the three panels in the accompanying chart show, MMT well describes what has actually occurred in the U.S. since 2008.

As the three panels in the accompanying chart show, MMT well describes what has actually occurred in the U.S. since 2008.

During this period, budget deficits and rising government debt have essentially offset a decline in the private sector debt-to-GDP ratio, with the result being that total debt as a percent of GDP has remained basically flat.

The minimal evidence of upward pressure on interest rates or inflation from the rising government debt makes it difficult to argue against the precepts of MMT, and has given populists like Trump and Democrat presidential hopefuls an opening to call for even larger deficits and lower rates.

Problems with MMT

The increasing prominence of MMT-oriented policy prescriptions has led to a backlash which highlights risks inherent in MMT including:

- MMT is dangerous because politicians get addicted to deficit spending. Every populist’s dream is to be able to throw money to the masses to buy support.

- A prolonged public sector spending spree will eventually lead to inflation and a reaction in the bond market. At high debt levels, rising interest rates could send the economy off a cliff.

- High debt levels are a drag on a country’s future growth rates (Reinhart & Rogoff).

- Longer term bonds contain a risk premium – the portion of interest which compensates the lender for risks of future repayment and rising interest rates. As debt ratios rise, risk premia and borrowing costs tend to rise.

- Running a time-limited deficit to offset a bout of economic weakness has its cost, but a new unfunded entitlement (“Medicare-for-All”) that creates an ongoing deficit is much riskier in that such spending is very hard to reduce if needed.

However, there has been increasing pushback to such puritanical notions, especially among some prominent Democratic economists. They assert that “the bond market will let the government know when the deficit is a problem” which demonstrably hasn’t happened yet. And the only inflation problem observable is that inflation remains stubbornly below the Fed’s 2% target.

In addition to Democratic partisans, some financial market types are also questioning how much danger of the growing U.S. debt represents. “Previous conventional wisdom about advanced economy speed limits regarding debt-to-GDP ratios may be changing,” said Mark Sobel, a former U.S. Treasury and International Monetary Fund official. “Given lower interest bills and markets’ pent-up demand for safe assets, major advanced economies may well be able to sustain higher debt loads.”

Lessons from Japan

The most direct test of MMT has been Japan. In 1999, the Bank of Japan became the first central bank to drive interest rates down to zero. A few years later, it pioneered the quantitative easing that the U.S. and Europe would later adopt. With multiple rounds of massive stimulus programs over the last 20 years, Japan’s government debt reached US$10 trillion in 2018 (250% of Japan’s GDP). But with equally massive asset purchases, the Bank of Japan has managed to keep 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yields below zero. Speculators have lost fortunes over the last 20 years betting that JGB yields would rise.

Observers have pointed to Japan to draw various and disparate conclusions regarding its fiscal and monetary policies. Perhaps the most incontrovertible conclusion is that in the context of a low growth economy and a domestic central bank that will purchase enough government debt to keep real interest rates below the growth rate of the economy, huge fiscal stimulus and the resultant government debt can persist for a very long time.

But those who would use Japan’s experience as evidence that pushing the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio a lot higher wouldn’t necessarily cause a crisis must acknowledge some important differences between the two countries. First, in contrast to the U.S., Japan runs a perennial current accounts surplus enabling Japan to rely largely on domestic capital. Second, the BOJ purchases about 70% of all Japan’s government bonds in contrast to the U.S. which is much more dependent on the kindness of strangers. And third and most importantly, Japan’s extreme fiscal and monetary policies have been both a cause and a result of a very low growth economy which contrasts markedly with the U.S. economy.

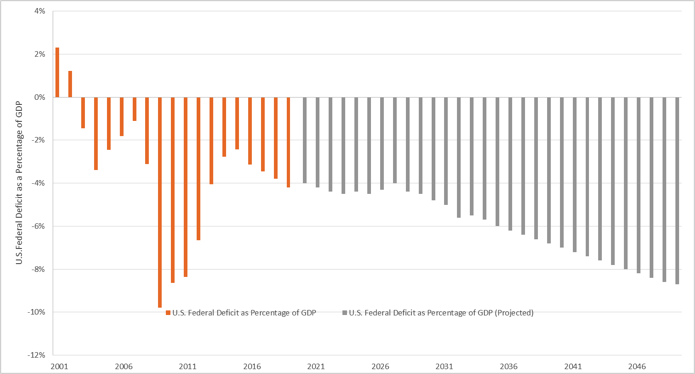

The Debt Outlook Moving Forward

Even with the U.S. economy at full employment, federal government deficits now exceed 4% of GDP and are expected to more than double to 9.3% by 2049 based on Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections as shown in the chart below. The CBO projects the federal debt to rise from 78% to 144% of GDP over the next 30 years. These projections assume no recessions and do not include either the huge unfunded federal liabilities or state and local government debt.

Figure 3: U.S. Federal Deficit as a Percent of GDP

- Source: Congressional Budget Office

Debt projections notwithstanding, it will be an uphill battle in the near term for those arguing against MMT policy prescriptions. Even those who used to talk about deficits are now silent. Trump has offered up budgets that cut discretionary spending but don’t touch entitlements which represent about 60 percent of the federal budget. No candidate is doing what it will take to come away from the 2020 elections with a mandate to put any breaks on spending. Hence, veteran Washington watcher Greg Valliere says investors should just sit back and get used to trillion-dollar deficits.[4]

So to return to the question posed in the title of this piece, U.S. federal deficits will again someday have a significant impact on capital markets, but that day is not here. Federal debt will become a major source of long-term inflation because there is no other easy way to address those massive liabilities. Hence, the path of least resistance is more spending and continued suppression of interest rates. Real rates will stay too low and government spending will push prices higher, conveniently eroding the value of the federal debt. Eventually, the delicate balance among budget deficits, debt levels, interest rates, and inflation will become unstable, but we don’t see that happening in 2020.

[4] Randall Forsyth, “Do Budget Deficits Matter? Not to Today’s Right or Left,” Barron’s, March 19, 2019

Implications for 2020

For now, major central banks are focused on battling deflation, and want inflation expectations to move closer to historical levels. However, after undershooting their targets since 2008, it is expected that this objective will probably require central banks letting inflation overshoot their targets. Thus, central banks are unlikely to tighten policy until late 2020 at the earliest.

Fiscal stimulus is bullish for economic growth and stock prices, but potentially bearish for bonds. If the nascent signs of a bottoming in global growth prove out as we expect, bond yields should grind higher in 2020. However, rising bond yields are unlikely to topple stocks this year to the extent that higher yields reflect stronger growth. Inflationary pressures in the U.S. are slowly building, but in an election year the Fed is unlikely to raise interest rates any time before late 2020.

Recessions are almost always caused by imbalances and tightened monetary policy. Prior to the 1991, 2001 and 2008 recessions, the private sector debt load had increased by 20.6%, 14.6% and 25.6% of GDP in the previous five years, far above the 1.4% increase of these last five years[5].

Our conclusions here are that the modest growth in private sector debt leaves room for government debt to grow without exerting significant near term inflationary pressure, and that the U.S. corporate sector will avoid a day of reckoning until interest rates rise significantly from current levels.

[5] BCA Research, Vol. 71, No. 6, November 19, 2019

Important Disclosures:

Past performance is no indication of future results. Investing in securities involves risk and the possibility of loss of principal. Investing should be based on an individual’s own goals, time horizon and tolerance for risk. The views of Miracle Mile Advisors, LLC (“MMA”) may change depending on market conditions, the assets presented to us, and your objectives. This research is based on market conditions as of the printing date. The materials contained above are solely informational, based upon publicly available information believed to be reliable, and may change without notice. MMA makes every effort to use reliable, comprehensive information, but we make no representation that it is accurate or complete. We have no obligation to tell you when opinions or information in this report change. MMA shall not in any way be liable for claims relating to these materials and makes no express or implied representations or warranties as to their accuracy or completeness or for statements or errors contained in, or omissions from, them. This report does not provide individually tailored investment advice. It has been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. The securities discussed in this report may not be suitable for all investors. MMA recommends that investors independently evaluate particular investments and strategies and encourages investors to seek the advice of a financial adviser. The appropriateness of a particular investment or strategy will depend on an investor’s individual circumstances and objectives. This report is not an offer to buy or sell any security or to participate in any trading strategy. In addition to any holdings that may be disclosed above, owners of MMA may have investments in securities or derivatives of securities mentioned in this report and may trade them in ways different from those discussed in this report. The value of and income from your investments may vary because of changes in interest rates or foreign exchange rates, securities prices or market indexes, operational or financial conditions of companies or other factors. There may be time limitations on the exercise of options or other rights in your securities transactions. Third-party data providers make no warranties or representations of any kind relating to the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the data they provide and shall not have liability for any damages of any kind relating to such data. The information and analyses contained herein are not intended as tax, legal or investment advice and may not be suitable for your specific circumstances; accordingly, you should consult your own tax, legal, investment or other advisors, at both the outset of any transaction and on an ongoing basis, to determine such suitability. Legal, accounting and tax restrictions, transaction costs and changes to any assumptions may significantly affect the economics of any transaction. MMA does not render advice on tax and tax accounting matters to clients. This material was not intended or written to be used, and it cannot be used by any taxpayer, for the purpose of avoiding penalties that may be imposed on the taxpayer under U.S. federal tax laws. The projections or other information shown in the report regarding the likelihood of various investment outcomes are hypothetical in nature, do not reflect actual investment results and are not guarantees of future results. Physical precious metals, real estate, emerging markets and other more opportunistic credit investments are subject to unique risks which include but are not limited to liquidity, rate volatility, currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, and the potential for political instability. In addition, the securities markets of many of the emerging markets are substantially smaller, less developed, less liquid and more volatile than the securities of the U.S. and other more developed countries. This report or any portion hereof may not be reprinted, sold or redistributed without the written consent of MMA.